The Trinity Site and the First Atomic Bomb

The first successful detonation of an atomic weapon on July 16, 1945 in a remote New Mexican desert had global and historic consequences. “A new thing had been born; a new control; a new understanding of man, which man had acquired over nature” (Isidore I. Rabi).

Even after the United States and its World War II allies accepted Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945, the conflict still raged in the Pacific with Japan. Japanese resistance was fierce as the United States painstakingly advanced toward Tokyo. As the allied forces moved island by island, fighting in sweltering jungle, both sides suffered heavy losses. It was at this crucial moment that the scientists of the secret American Manhattan Project began planning for a test that would not only change the course of the war, but also the future of international relations.

The United States, in collaboration with allied Great Britain, had been developing an experimental master weapon since August 1942. Code-named “The Manhattan Project,” this highly secret endeavor largely took place in Los Alamos, New Mexico although there were participating teams at Oak Ridge, Tennessee and Hanford, Washington. In this inaccessible New Mexican desert, hundreds of physicists, chemists, engineers, and military personnel gathered in secret to theorize and create the deadliest weapon known to man.

By the end of 1944, there were two designs and two bombs, Little Boy and Fat Man. Little Boy used a gun-type fission design which shot uranium 235 at itself to reach supercritical mass, resulting in the single largest explosion of its time. The Los Alamos scientists were confident that this design would work and did not want to waste any precious material on a test. Little Boy had used all available U235, so any test would deplete the United States’ supply and would require too much time for the project to regenerate at its Oak Ridge site. Little Boy would go on to be dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945 and become the first nuclear bomb used in warfare.

On the other hand, Fat Man utilized an implosion design with explosives surrounding the highly reactive plutonium core. The idea was that the inward-facing explosives would trigger an explosive reaction of the plutonium and result in a larger blast than its Little Boy uranium counterpart. The scientists were less confident in this design. Plutonium had only been discovered at the end of 1940, and the implosion method was difficult to master. If each explosive was not uniform in strength and distance, the correct reaction would not begin, and the overall impact would decrease. Due to these doubts and the easier access to plutonium, the Los Alamos scientists decided to test “The Gadget.”

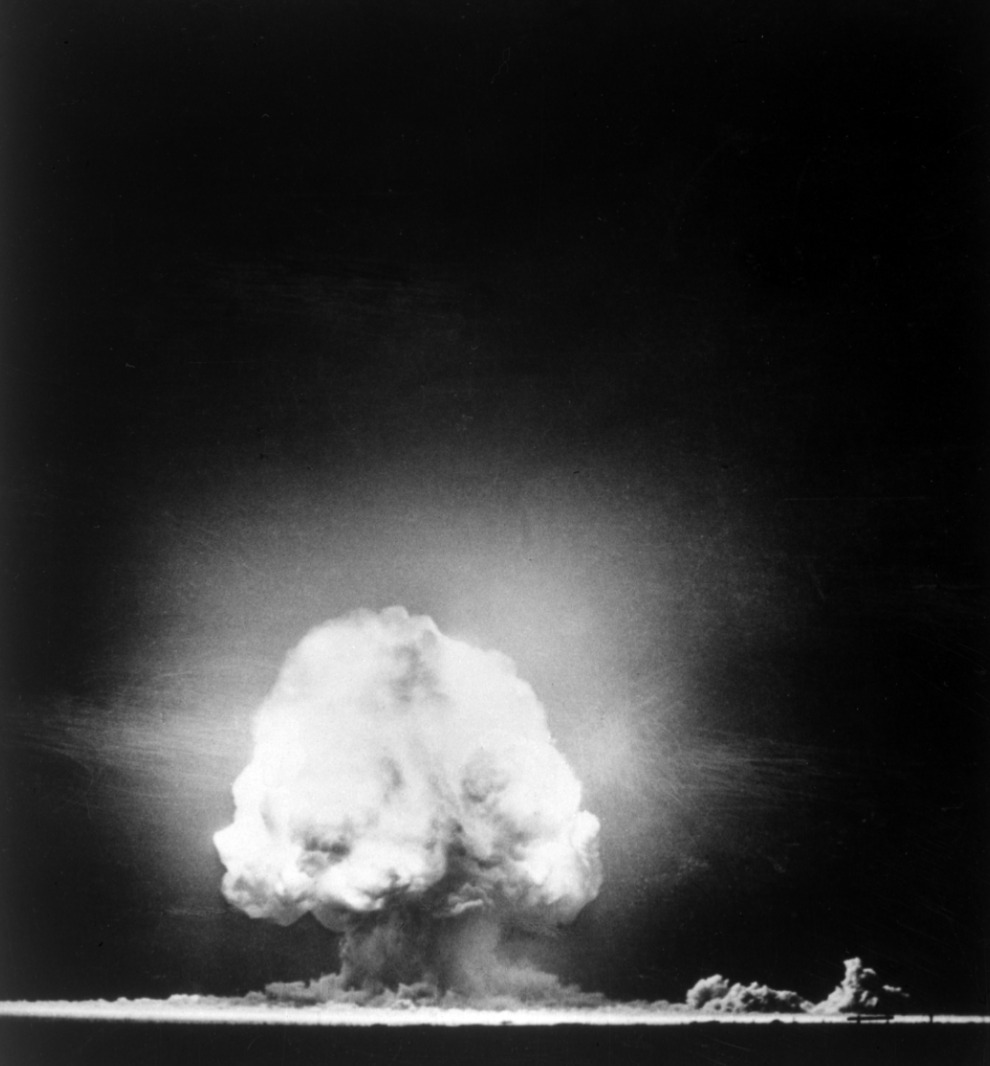

The first step was finding somewhere to detonate a 10,000 ton bomb without alerting the international community. They decided on a stretch of high desert between New Mexico and Texas called Jornada del Muerto, translated as “Journey of Death.” It was later named the Trinity Site, likely inspired by Robert J. Oppenheimer’s interest in the Hindu concept of the three gods of preservation, destruction, and creation. On May 31, 1945, the requisite shipment of plutonium arrived in Los Alamos from the Hanford facility and scientists began to assemble Fat Man. Up to this point, Los Alamos had not housed a significant supply of plutonium, so all work on Fat Man was done speculatively or at miniscule scales. Working at a harried pace, scientists and engineers readied and transported a plutonium core to Trinity by July 13. Harry Truman, newly inaugurated President of the United States, wanted the test completed before the Potsdam conference with Churchill and Stalin on July 17, but weather conditions made it difficult for the scientists to comply. Finally, at 5:30 am on July 16, “The Gadget” detonated.

Many reactions have been recorded describing the physical experience as well as moral and philosophical implications of the detonation. The light was so powerful that Georgia Green, a blind student miles away at the University of New Mexico asked “What’s that?” Physicist Isidore I. Rabi, who observed from ten miles away at base camp wrote, “Suddenly, there was an enormous flash of light, the brightest light I have ever seen or that I think anyone has ever seen. It blasted; it pounced; it bored its way right through you. It was a vision which was seen with more than the eye. It was seen to last forever.” Rabi also acknowledged the historic and philosophical weight of the moment, “A new thing had been born; a new control; a new understanding of man, which man had acquired over nature.” Alongside confusion and fear expressed by some locals and trepidation expressed by some Los Alamos scientists, there was also great enthusiasm and excitement. Project officials immediately sent a coded telegram announcing the “satisfactory operation” to Truman, just before his meeting with Churchill and Stalin.

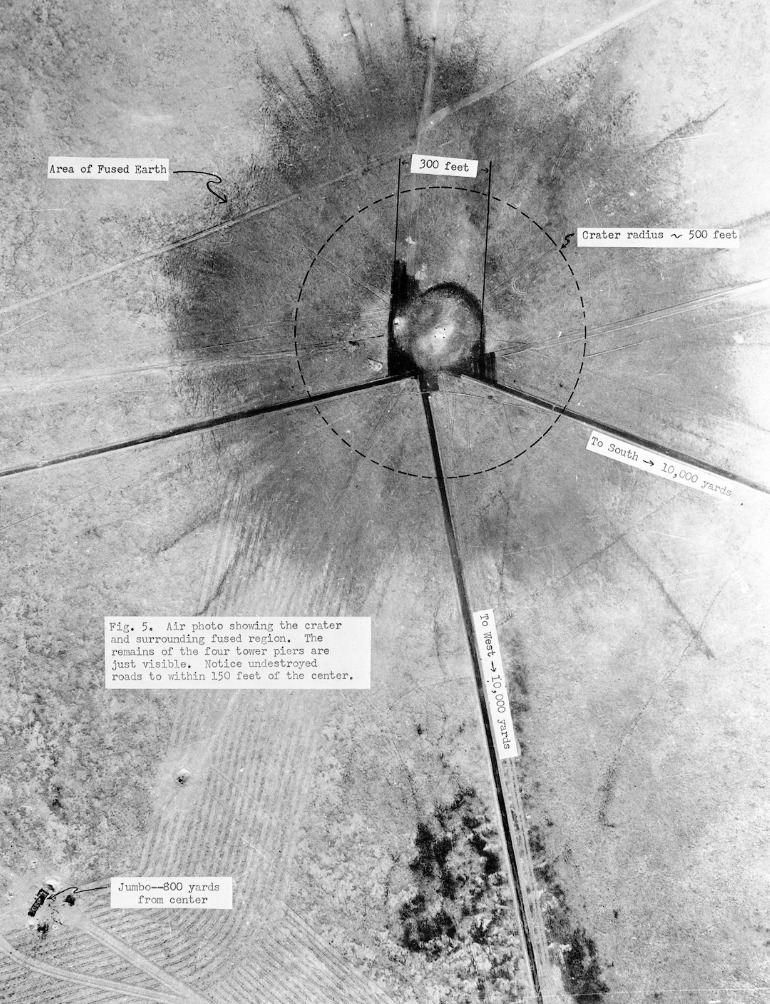

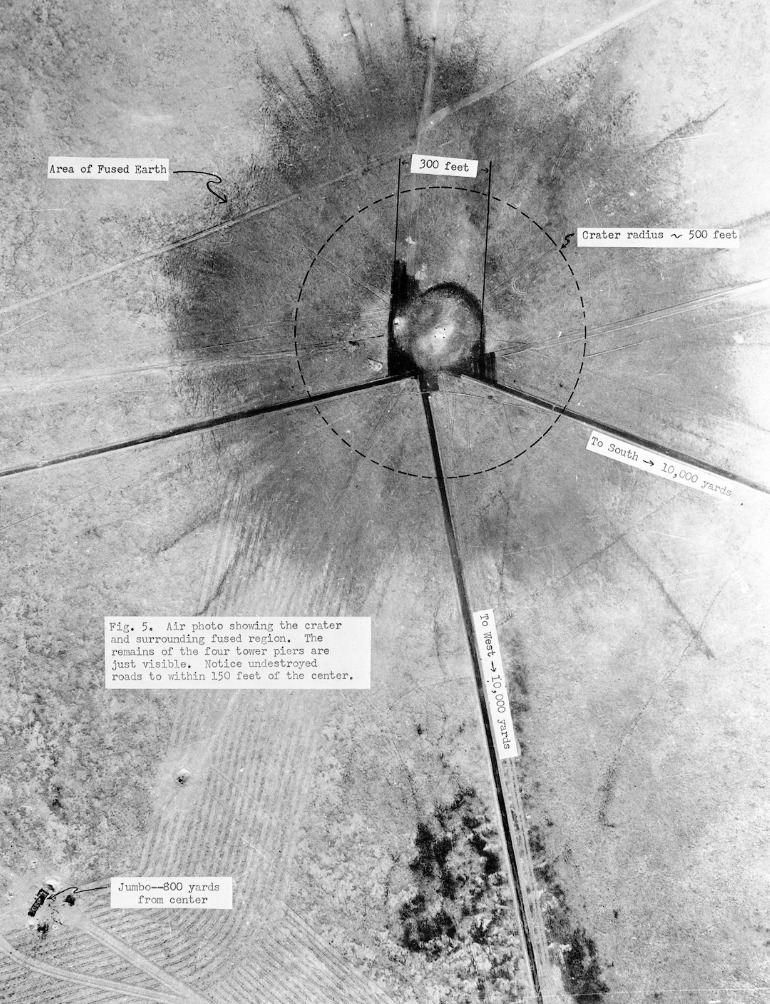

Back at the Trinity site, the scientists emerged from their safe havens and inspected the damage. The Gadget had destroyed every living thing within 1,200 feet of ground zero and disintegrated the steel tower on top of which it had been placed. It was, in the words of General Groves, “successful beyond the most optimistic expectations of anyone” and even larger than Little Boy. Because of its success at the Trinity Site, the Fat Man model would later be dropped on Nagasaki on August 9th, three days after Little Boy obliterated Hiroshima.

Today, Trinity remains a highly radioactive site. Visitors are only allowed to visit two days a year. There are replicas of the bomb casing and the tower. Part of the original crater remains and reveals pockets of Trinitite, a green residue of highly radioactive sand particles melted by incredible temperatures into a glass-like substance. It can only be found at the Trinity Site and is illegal to collect for health concerns. Here, the first man-made atomic weapon detonated which aided in ending WWII and ushering in the age of atomic weaponry and mutually assured destruction. This continues to define international relations today.

Images