Jewish Contribution to the Manhattan Project

Jewish participation in the Manhattan Project, particularly in Los Alamos, was an essential part of the operation's success. They continued to support their country despite local discrimination and the tragedy of World War II occurring abroad.

The United States’ development of the first atomic bomb would not have been possible without the contribution of Jewish Americans and Jewish refugees who fled Nazi Germany and war-torn Europe throughout the Manhattan Project. In August of 1939, Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, and Enrico Fermi drafted and sent a letter to President Roosevelt via Alexander Sachs, warning the President of the potential use of atomic power in weaponry. This, in addition to another letter sent by British-Jewish scientists, led Roosevelt to form an advisory committee on uranium and, eventually, create the Manhattan Project.

Significantly, every person involved in the drafting and deliverance of this letter were Jewish or had close Jewish family members. Of the four involved, three were European refugees. Einstein was from a family of German Ashkenazi Jews and fled to the United States in 1933. Szilard was from a Hungarian Jewish family and fled to England in 1933 and then the United States in 1938. Fermi, while himself not Jewish nor German, was married to a Jewish woman which required him and his family to flee his home of Italy in 1938. Sachs was American-Jewish and an important advisor to President Roosevelt. All were impacted by the anti-Semitism of Germany and were respected and prominent enough to sway the President of the United States into forming a committee. Subsequent letters and information, much of which was provided by Jewish scientists, followed and increased the breadth of the project.

Jewish involvement in the Manhattan Project burgeoned as the war continued. J. Robert Oppenheimer, a young American Jew, was placed as the head of the Los Alamos branch of the Manhattan Project. He created four divisions in the Los Alamos lab, with the T-division, the theoretical division, being the most important. Of the 86 members in this division, 18 were Jewish—almost 21%. Even more impressive, of the eight groups in 1945, five were led by Jewish scientists such as Richard Feynman, Hans Bethe, and John von Neumann. Although Jews only constituted around .05% of the US population at the time, they made up a significant portion of the scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Jewish involvement in the Manhattan Project, as well as the project itself, were not known by the American public, and antisemitic prejudice was commonplace. In the 1920s, before J. Robert Oppenheimer attended, the president of Harvard, A. Lawrence Lowell, called for a quota of Jews to keep their presence sparse in the university. Even in Los Alamos, where Jewish scientists were important pioneers of the Manhattan Project, General Leslie Groves, the project’s military leader, stated, “I don’t like certain Jews, and I don’t like certain well-known characteristics of theirs.” Some Jewish scientists, such as Leo Szilard, were tailed by the FBI and noted for their “Jewish extraction” and “foreign tongue.”

At the same time, Los Alamos was a relative haven for these Jews. They were allowed in the upper echelons of decision-making and they were not stripped of titles or rewards because of their background. Ellen Bradbury Reid, an Anglo child in Los Alamos recalled, “I would not say [it was] a utopian situation, but. . . now I realize there were a lot of Jewish people, the European Jewish community who were there. I had no idea. . . [we] were all sort of in the same soup.” Despite prejudice, Jewish scientists were largely able to find footing in Los Alamos and thrive in the project. Jewish scientists in the Manhattan Project made a substantial and powerful impact in crafting the bombs which would end the war that, in total, killed over six million Jews.

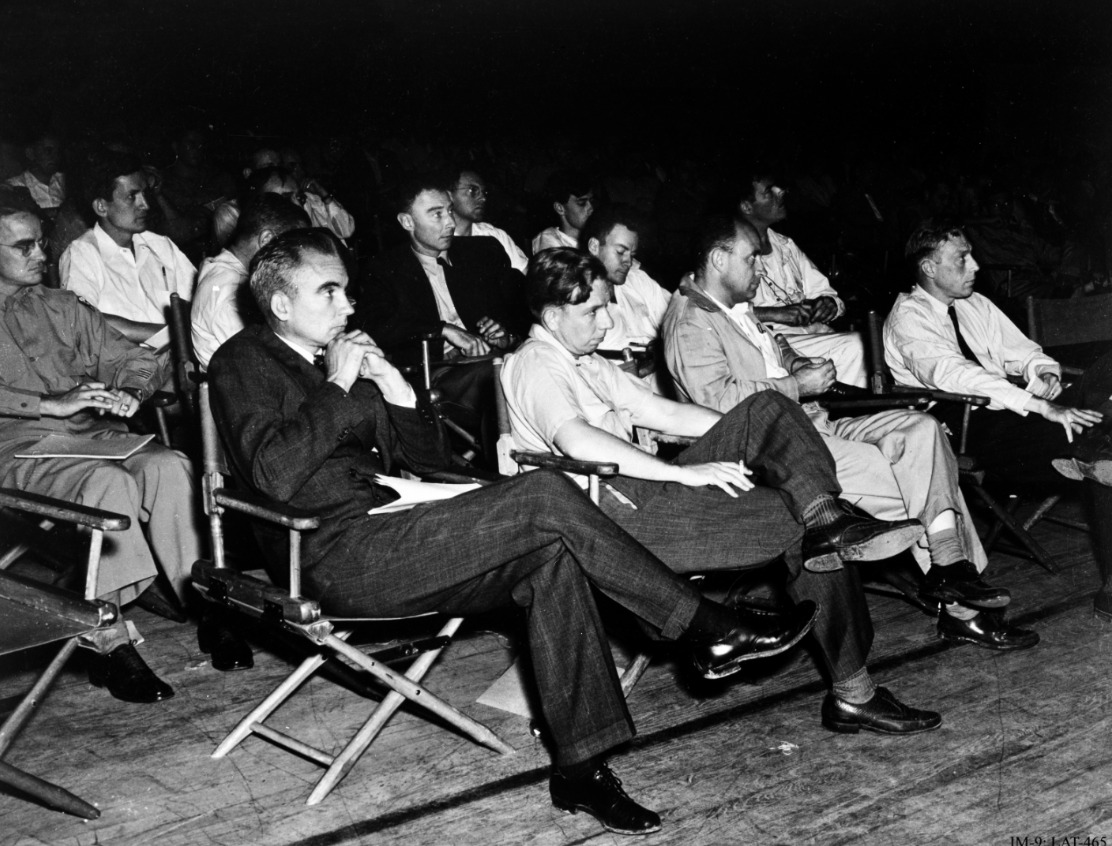

Images