Japanese Internment Experiences in Utah vs. Arkansas

Japanese internment is an unfortunately an event in America’s history, too often glossed over. Many people are unaware of the unjust imprisonment of many Japanese families in the U.S. during World War II. No matter the location, Japanese families and individuals experienced hardships in internment camps; hardships that differed depending on the location of the camp.

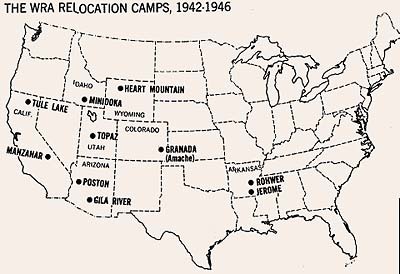

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, President Roosevelt issued executive order 9066, calling for the relocation of Japanese Americans living within the U.S. Following this order, ten relocation camps were created within the United States; eight located in the western region, two in the south. The differences in conditions of camps in the west versus the south can be effectively illustrate by comparing the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah, to the the Jerome and Rohwer camps, located in the southern Arkansas delta region.

Residents of both Topaz and the Arkansas camps experienced great hardship when faced with climates drastically different from the temperate California environment. The extreme desert temperatures at Topaz frequently fluctuated between below freezing at night to over 90 degrees in midday, which inflicted great hardship upon its residents who were exposed to the elements in partially completed barracks. In central Utah desert, internees were required to perform labor essential to cultivate agriculture in their barren, dusty environment. One resident described this when he stated, “They made cowboys out of the Japanese.”

While Utah internees faced hardships in the form of weather extremities, the plight of Arkansas internees was attributed primarily to their miserable swampy environment; one that was unfamiliar to California natives. The locations of the Jerome and Rohwer camps were outliers to the western location of the other eight camps. These camps were built due to the availability of land that had been abandoned by landowners who were overwhelmed at the prospect and draining and clearing the unrelenting swampland. This feat was left to Japanese internees, who were tasked with the responsibility of draining and clearing the land (Ward).

Japanese internees in Utah and Arkansas also experienced drastically different experiences concerning interactions with those outside the camps. The presence of internees in Arkansas presented a unique problem to the racially stratified Jim Crow South. The sudden appearance of a new ethnic minority in a society previously separated into primarily black and white races, was the source of confusion and objection among many native residents. Fierce prejudice arose among many Arkansas natives, including Governor Homer Adkins.

Despite the compliance of states housing the other camps, Adkins staunchly refused to allow Japanese students to enroll in Arkansas universities, and in many cases refused to allow internees to work on projects outside of the camp (Ward). When referring to the prospect of Japanese working outside the camp Adkins once stated, “I don't mind them leaving to work in other states, but as a matter of policy I am not going to recommend that Japanese work in any capacity in this state." Adkins’s commitment to confine internees in their camps was a prejudiced policy not replicated at Topaz, where students were allowed to attend outside universities, and many workers were granted release to work in areas surrounding the camp in areas as far away as Provo.

Images